Newgrange Excavation Report Critique by Alan Marshall

Newgrange: Archaeology, Art and Legend by Michael, J, O'Kelly.Summary of excavations at Newgrange

This monograph details excavations of 1962-1975 at the Neolithic chambered passage tomb of Newgrange, Co. Meath, Ireland. Newgrange lies on the Boyne River approximately 50km north of Dublin and is part of a tomb complex (O'Kelly, 1982, 13). The project was financed by the Irish Office of Public Works as the monument had become neglected. Nature and unsupervised visitors had taken their toll leaving the passage orthostats worn and dangerous. The mound too was tattered by animal burrows, visitors and tree roots so a programme of repair was devised. This incorporated careful survey to establish the monuments original form and consolidation of the tomb to its former state. Excavation was carried out by Bord Fáilte volunteers and various universities including Cork (O'Kelly, 1982, 10-11).Excavation included initial exploratory trenches over a 30º section to establish original ground levels and the nature of material which had slumped from the mound. A kerb of megaliths was found with a collapsed quartz and granite façade instigating further seasons of work (O'Kelly, 1982, 11). The main excavations involved clearing approximately 1/3 of the slump running either side of the south-eastern passage entrance and included the surrounding stone circle, a band of post holes and a clay bank (O'Kelly, 1982, 21-22). Beaker settlement was found along with elaborate carvings on many of the kerbs. The revetment was reconstructed with concrete support (O'Kelly, 1982, 110) and the cairn reshaped (see fig. 2).

The second area of excavation was the passage itself which was consolidated and protected with concrete capping and reinforcing to halt movement (O'Kelly, 1982, 112). This necessitated an embrasure cutting providing further information of the cairn construction along with megaliths of the chamber (O'Kelly, 1982, 89). The passage itself presented more megalithic art, many hidden from view, and a unique 'roof box' which is aligned to the winter solstice (O'Kelly, 1982, 21). Other test trenches were excavated around the cairn to gauge its construction. The result is a restored passage tomb, secure for tourism and exhibiting O'Kelly's interpretation of its original form. Michael O'Kelly sadly died prior to publishing so sections of the report are compiled by his wife Claire.

Fig. 2: Contour plan of Newgrange's cairn and passage with the 1962-1975 trench positions marked (O'Kelly, 1982, 15).

Summary of this critique

The report will now be examined in roughly chapter order assessing how the sections are arranged, written and presented before a more general critique of the report as a whole is addressed. This will consider the organisation of illustration and text and the reliability of O'Kelly's Interpretation. A summary of whether the report meets its aims successfully will conclude.Introduction and background

The introduction makes the location of Newgrange very clear with scaled illustrations and maps (see Fig. 1). Only a grid reference is lacking (suggested by IAI guidelines) (IAPA, 2000, 20). Topography of the site is dealt with at length describing its ridge location and views of the Brú na Bóinne area. It identifies associated tombs and monuments although does not mention any previous archaeological work from them (O'Kelly, 1982, 13) and establishes that many more are likely to have once existed. The contour survey is reproduced but is too small to be of use (see fig. 2 approximately original size) and a simple site plan may have proved more legible. The geology of the region is notably absent and only mentioned in interpretation of how Neolithic builders sourced their materials 10 chapters later (O'Kelly, 1982, 116). The actual structure of the cairn however is pre-empted and would sit better in the excavation section. There is brief mention of previous work at Newgrange which was certainly minimal prior 1962. Victorian repair work is alluded to although O'Kelly states that all documentation relating to the work has been lost (O'Kelly, 1982, 23). The remaining antiquarian accounts and folklore therefore take centre stage serving as both historical sources and scant archives of work.Historical sources

The visibility of the monument means that historical accounts are wide ranging and Newgrange's national importance means that O'Kelly elects to cover it in two chapters: History and Newgrange in Irish literature.The first compiles sources from 1699 to 1939 which O'Kelly interprets reasonably, for example equating Charles Campbell's 1699 'broad flat stone, rudely carved' as the entrance stone with its art. He assesses the sources for reliability, exercising caution with some such as the potential misdating of the Annals of Ulster (862AD) (O'Kelly, 1982, 24-25) and frequently compares contemporary sources to make evidence not visible today more conclusive. Conversely he cross-references antiquarian notes to his own findings and assesses their validity that way, e.g. the Office of Public Works' props and shores are identified (O'Kelly, 1982, 38-39). Finally the sources are examined to identify a gap in knowledge (mainly cairn construction) which justifies the modern excavation as research alongside repair (O'Kelly, 1982, 42).

The second chapter is less integrated into the report. It surveys Newgrange's part in mythology and folklore, ancient and modern, and its importance as a monument of Irish identity. The section overflows with Irish pride (deservedly) to the point of nationalism, especially as the Boyne Valley is of political importance from later events (O'Kelly, 1982, 44-45), but O'Kelly treats the myths rationally and extracts archaeological evidence form them that support the cultural value of his reconstruction perfectly.

Methodology and excavation

The circumstances of the project are reflected in the methodology and explained in detail. The approaches used are simple but logical and were reviewed as work proceeded (see fig. 3). The only improvement would be to have included greater pre-excavation survey. The topographic survey of the mound and surroundings (mentioned above) is present but perhaps ground penetrating radar or similar would shed light on the 2/3 remaining unexcavated (although it is acknowledged the project was carried out in 1962), for example, a similar excavation at Knowth tomb nearby discovered 2 passages (May, 2002, 328). The report reviews the excavation in 5 stages based on location rather than seasons of work which is a great improvement on the scattered approach of interim reports (O'Kelly, 1964, 1968, 1969) although only possible following completion.

Fig. 3: Part of the excavation plan showing how methodology changed to suit changing needs and conditions

O'Kelly's analysis of stratification in the cairn is thorough, presented free from jargon and supported well by detailed section drawings. These would however benefit from being larger and using shading to separate distinct layers/stone types (O'Kelly, 1982, 69). Throughout the stages he makes the objectives plain before working through the findings. These often include near demolition of the monument before it is reconstructed and at times seems a little harsh to modern eyes. However, given the national status of Newgrange and its yearly number of visitors, it is probably acceptable if adequately recorded which seems to unerringly be the case.

Restoration

The post excavation section is comprised solely of construction and restoration of the monument. There is no finds analysis or similar work included here which seems a large oversight. That said reconstruction is obviously the key purpose of the excavation and demands reasonable space.The choice of how to restore the monument is more problematic. It is largely single phase so the period to present is not addressed but the construction of the revetment is debated. O'Kelly bases his interpretation on an engineers report and experimental reconstructions on site which seem convincing but details such as the position of granite pebbles caused controversy at the time (O'Kelly, 1982, 110) (see fig. 4). P, Giot criticises it as 'looking like a sort of cream cheese cake with dried currents distributed about' (Giot, 1983, 149). In O'Kelly's defence he makes clear in the report that he is only reconstructing using the best evidence available and it may be open to criticism (O'Kelly, 1982, 110).

Conclusions and interpretations

Interpretation is split neatly into Neolithic construction methods and a discussion of the 'Cult of the Dead'. The former uses experimental archaeology, e.g. the lifting and positioning of passage cap stones to suggest Neolithic methods which is intriguing and well supported by the evidence found on site (O'Kelly, 1982, 112). A sizable section on labour and man-hours is included in which O'Kelly rebukes the unsupported statistics of Frank Mitchell but then uses Mitchell's work to re-evaluate Newgrange's construction (O'Kelly, 1982, 117). This seems largely pointless and does not add to the monuments understanding. The more constructional aspects are better supported and interpreted, but it is unfortunate that O'Kelly does not widen the analysis to include the Brú na Bóinne landscape as a whole.The second conclusion explores this in greater detail looking at other passage graves and their similarities but quickly reverts to studying the physical structure of the 'roof box'. This alignment is analysed from various angles and the significance of it proved conclusively by construction, mathematics and astrology (O'Kelly, Patrick, 1982, 124). Less can be said of other enigmas such as an area of stripped turf around the cairn which is examined and resolved as far as date and scope but not purpose (O'Kelly, 1982, 127). Dating in general is addressed here referring to specialist reports in the appendix and appears to be firmly fixed to 2500BC. This is supported by numerous C14 deposits but no artefacts (O'Kelly, 1982, 145, 230-231).

In summary the conclusions reached are extremely factual which decode the tomb realistically but leaving the reader wondering about the wider Neolithic environment of the Boyne Valley and the people who lived and worshiped at its monuments.

Specialist reports

The report contains 11 specialist reports presenting all the information for aspects other than the monument itself. These are wide ranging and informative and enhanced by clear illustration (particularly the finds section). They are similarly typeset making comparison easy, but some resort to technical terminology and become impenetrable, e.g. the pollen analysis tables contain only Latin names in chart format where common names and pictograms would be more accessible (Groenman van Waateringe, Pals, 1982, 220-221). Only one specialist mentions the archive's deposit (O'Kelly, 1982, 186) which incidentally is not mentioned elsewhere in the whole report.The main criticism of the specialist reports is that they are presented largely as raw data. This is not normally detrimental as they are integrated into the excavation interpretation but this does not apply here and there are few conclusions drawn from the analysis. This makes the work seem irrelevant to the main body of work.

Appendix F is particularly puzzling with 2 separate mollusc reports reaching comparable conclusions and neither being used in the interpretive stage (Van der Spoel, 1982, 226 and Mason, Evans, 1982, 227).

A large section appears as a pictorial corpus of the megalithic art. This, although not convincingly integrated with the main text, is a useful report. It is approached objectively and thoroughly presenting differing views of the carvings and their position and explaining methodology clearly (O'Kelly, 1982, 152).

The report as a whole

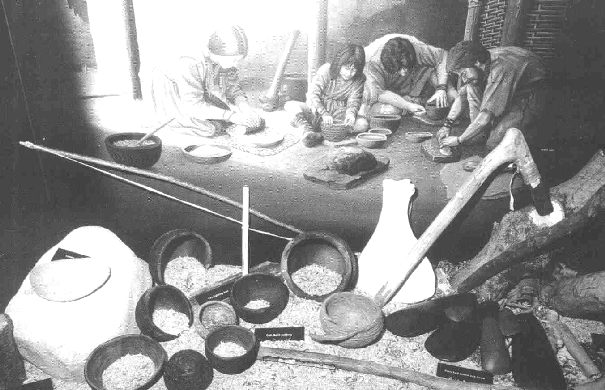

The monograph is logically laid out and broken into distinct but sequential chapters. These are small enough, and with enough subheadings and cross referencing, to find particular aspects without undue searching. The exceptions to this (mentioned above) are the specialist reports which read as unrelated papers and contribute little to the discussion of the site. This is largely due to the publishing date as further interpretation is easily accessible in modern synopses of O'Kelly's work. For example wider implications such as Neolithic housing and life in the Boyne Valley are presented in the modern visitors centre and guide book (see fig. 5) (Keane, 2003, 36-39). This goes to show that the initial data was sufficient to provide this aspect and a conscious decision was made to concentrate specifically on the tomb construction. O'Kelly himself also published later work on the Beaker phase of the site which provided more artefacts and thus a wider interpretation of settlement than Neolithic (O'Kelly et al, 1983).

Fig. 5: Newgrange visitors centre display showing the wider interpretations of the Boyne Valley Neolithic settlement. This is notably absent from O'Kelly's report (Keane, 2003, 36).

Illustration and photography in the book is exquisite. There are many colour photos and although some provide an arty, coffee table book feel they back the discussion beautifully. The archaeological photography is of mixed proficiency. Many do not contain scales or do not state what the scale is which decreases their analytical use (see fig. 6). However all are clear and provide a full diary of excavation. The illustration diagrams are unfortunately not presented to their full potential. They are intricate and thorough so suffer from being reproduced too small to read accurately, the redeeming factor is that they are integrated well in the text so their relevance is clear. One particularly good feature of the report is the use of margin notes to guide the reader to any relevant plates or illustrations but without breaking the flow of the text.

The lack of reconstruction drawings is understandable as the monument itself fills this role. However numerous criticisms of O'Kelly's interpretation have been bought forward. The most pertinent is probably George Eogan (director at Knowth) who disputes the façade construction (see fig. 4) claiming it would not stand without concrete support. This has led to Knowth's alternative quartz arrangement remaining 'in situ' on the ground (May, 2003, 333). O'Kelly does not present alternatives such as this in his report which is a shame but he does back his theories adequately. The absence of discussion has resulted in the long-term acceptance of his reconstruction, sometimes blindly (see fig. 7). It is difficult to tell if O'Kelly adhered to standards of practice as the IAI were not in existence during the excavation but his report is largely written following their guidelines with only minor oversights (IAPA, 2000).

Fig. 6: Photographs from the monograph with no scale and a indeterminate scale bar which decrease their usefulness (O'Kelly, 1982, 50, 130).

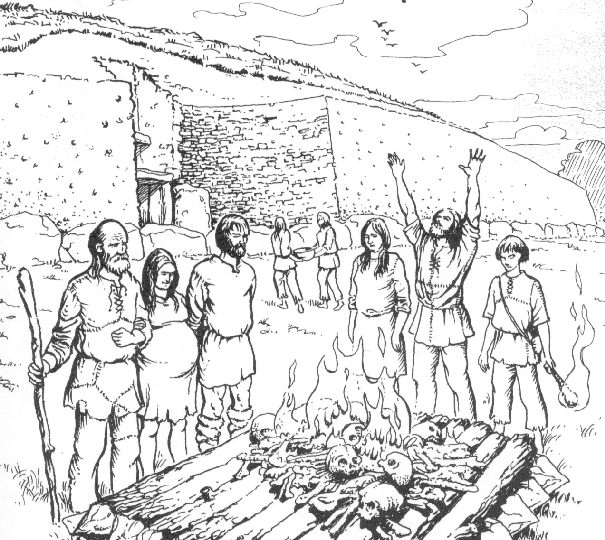

Fig. 7: Reconstruction of cremation at Newgrange which inadvertently depicts the facade complete with unoriginal visitor access designed by O'Kelly 1972, not Neolithic settlers (Exploring Newgrange by Liam Mac Uistin, 1999, p47).

Summary

O'Kelly sets out to provide more than an excavation report and notes that it has transformed into ' a review of the history of research at Newgrange, a survey of its place in history and the corpus of the art and objects found there' (O'Kelly, 1982, 8). With these objectives in mind it can only be concluded that the book succeeds admirably. O'Kelly produces a work of facts not theory, much in line with his fieldwork methods (Giot, 1983, 150). He was undoubtedly a processualist and thus presents a tested, functional interpretation. This makes for a detailed, accurate report which includes technical construction mixed favourably with historical magic. The major downfall is the adherence to the tomb fabric and lack of contemplation of Newgrange's social and cultural position in the Neolithic. Much of this is a criticism of the archaeological discipline as a whole rather than O'Kelly's writing and on balance it is concluded that Newgrange: Archaeology, Art and Legend provides an excellent chronicle of the excavations at this important site.Bibliography

- Giot, P. 1983. Reviews: Newgrange. Antiquity Vol. 57. pages 149-150.

- Groenman van Waateringe, W & Pals, J. 1982. Pollen and Seed Analysis. In O'Kelly, M. 1982. Newgrange: Archaeology, Art and Legend. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Irish Association of Professional Archaeologists. 2000. Guidelines for Archaeologists.

- Keane, E. 2003. Brú na Bóinne. Wicklow: Archaeology Ireland.

- Mason, C & Evans, J. Land Molluscs 2. In O'Kelly, M. 1982. Newgrange: Archaeology, Art and Legend. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Mac Uistin, L. 1999. Exploring Newgrange. Dublin: O'Brien Press.

- May, J. 2003. Eogan of Knowth. Current Archaeology Vol. 188. Pages 328-334.

- O'Kelly, C. 1982. Corpus of Newgrange Art. In O'Kelly, M. 1982. Newgrange: Archaeology, Art and Legend. London: Thames & Hudson.

- O'Kelly, M. Cleary, R. & Lehane, D. 1983. Newgrange: County Meath, Ireland: The late Neolithic/ Beaker period Settlement. Oxford: B.A.R.

- Patrick, J. 1982. The Cult of the Dead. In O'Kelly, M. 1982. Newgrange: Archaeology, Art and Legend. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Van der Spoel, S. Land Molluscs 1. In O'Kelly, M. 1982. Newgrange: Archaeology, Art and Legend. London: Thames & Hudson.

Boyne Valley Private Day Tour

Immerse yourself in the rich heritage and culture of the Boyne Valley with our full-day private tours.

Visit Newgrange World Heritage site, explore the Hill of Slane, where Saint Patrick famously lit the Paschal fire.

Discover the Hill of Tara, the ancient seat of power for the High Kings of Ireland.

Book Now

Immerse yourself in the rich heritage and culture of the Boyne Valley with our full-day private tours.

Visit Newgrange World Heritage site, explore the Hill of Slane, where Saint Patrick famously lit the Paschal fire.

Discover the Hill of Tara, the ancient seat of power for the High Kings of Ireland.

Book Now

Home

| Newgrange

| Knowth

| Dowth

| Hill of Tara

| Fourknocks

| Loughcrew

| More Places

| Labyrinths

| Local Info

| Art Works

| Articles

| Images

| Books

| Links

| Boyne Valley Tours

| Contact