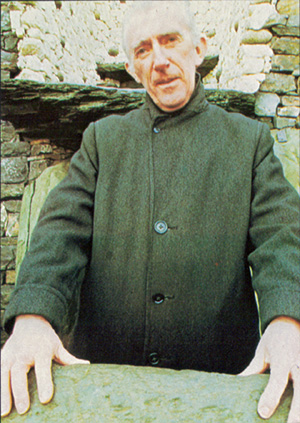

Professor Michael J. O'Kelly (1915-1982)

Professor O'Kelly

excavated and restored Newgrange

from 1962 to 1975. He discovered that the builders of Newgrange deliberately oriented the passage so

that each year around midwinter, the rays of the rising sun would shine through a special aperture to illuminate the chamber.

Professor O'Kelly

excavated and restored Newgrange

from 1962 to 1975. He discovered that the builders of Newgrange deliberately oriented the passage so

that each year around midwinter, the rays of the rising sun would shine through a special aperture to illuminate the chamber.

Professor O'Kelly was a respected teacher, writer and practicing archaeologist, he was Professor of Archaeology at University College Cork from 1946 until his untimely death in 1982.

This photography and the following article are from Arthur C Clarke's Mysterious World published in 1980.

Nothing about stone circles is more mysterious or magical than the question of their astronomical alignments. In recent years theories about these have overshadowed all other discussion. The idea that some circles were aligned to the sun, moon or even the stars is not new.

It certainly dates back to the eighteenth century when William Stukeley noted in his book on Stonehenge that the stones were aligned to the Midsummer sunrise. At the beginning of this century, the astronomer, Sir Norman Lockyer, published a set of alignments which he had discovered during a survey of Stonehenge. The simplest and most dramatic evidence that prehistoric man studied and exploited the movements of celestial bodies comes not from stone circles but from two magnificent chambered tombs one in Ireland, the other on Mainland in Orkney.

Newgrange Tumulus is sited on the banks of the River Boyne, a few miles down narrow country lanes from the city of Drogheda in the Irish Republic. Since being restored, its great curving mound, faced with brilliant white quartz and inset with oval granite boulders, reveals it to have been one of the architectural wonders of ancient times. Although it is little known outside Ireland, Newgrange has a special significance: it was built in about 3250 BC, about 500 years before the Pyramids of Egypt. It is therefore the oldest existing building in the world.

Five thousand years ago, the people who farmed in the lush pastures of the Boyne Valley hauled 200,000 tons of stone from the river bank a mile away and began to build Newgrange. At the foot of the mound, they set ninety-seven massive kerbstones and carved many of them with intricate patterns. Inside, with 450 slabs, they built a passage leading to a vaulted tomb, and placed a shallow basin of golden stone in each of its three side chambers.

By the time one of Ireland's leading archaeologists, Professor Michael O'Kelly of University College, Cork, came to excavate and restore Newgrange in the 1960s, the tomb had been a tourist attraction for more than 250 years. (It had been discovered by chance in 1699.) So it was hardly surprising that he was able to find only a handful of the bones which the tomb and its stone basins must have been designed to hold. But despite the visitors who had walked up the stone passageway into the corbelled chamber for more than two centuries, the most spectacular secret of Newgrange still awaited discovery.

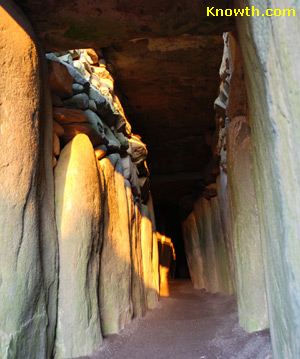

As O'Kelly's team of restorers removed the grass and weeds from the mound, they came across a curious rectangular slit above the door. It was half-closed by a square block of crystallized quartz, apparently designed to work as a shutter. There were scratches on the quartz: clearly it had often been slid to and fro, providing a narrow entrance to the tomb above the main door, which was firmly sealed with a 5 ton slab of stone.

But what was the slit for? It was too small and too far from the ground to be an entrance for people. Professor O'Kelly remembered a local tradition which said that' the sun always shone into the tomb at Midsummer. Perhaps the 'roofbox', as it came to be known, was designed to admit the summer sun to the tomb without the entrance stone having to be moved. 'But it was quite obvious to us that it couldn't happen at Midsummer because of the position of the sun' says O'Kelly. 'So if the sun was to shine in at all, the only possibility would be in Midwinter.'

In

December 1967, Michael O'Kelly drove from his home

in Cork to Newgrange. Before the sun came up he was at the tomb, ready to

test his theory. 'I was there entirely alone. Not a soul stood even on the

road below. When I came into the tomb I knew there was a possibility of

seeing the sunrise because the sky had been clear during the morning.'

He was, however, quite unprepared for what followed. As the

first rays of the sun appeared above the ridge on the far bank of the

River Boyne, a bright shaft of orange light struck directly through the

roofbox into the heart of the tomb. 'I was literally astounded. The light

began as a thin pencil and widened to a band of about 6 in. There was so

much light reflected from the floor that I could walk around inside

without a lamp and avoid bumping off the stones. It was so bright I could

see the roof 20ft above me.

In

December 1967, Michael O'Kelly drove from his home

in Cork to Newgrange. Before the sun came up he was at the tomb, ready to

test his theory. 'I was there entirely alone. Not a soul stood even on the

road below. When I came into the tomb I knew there was a possibility of

seeing the sunrise because the sky had been clear during the morning.'

He was, however, quite unprepared for what followed. As the

first rays of the sun appeared above the ridge on the far bank of the

River Boyne, a bright shaft of orange light struck directly through the

roofbox into the heart of the tomb. 'I was literally astounded. The light

began as a thin pencil and widened to a band of about 6 in. There was so

much light reflected from the floor that I could walk around inside

without a lamp and avoid bumping off the stones. It was so bright I could

see the roof 20ft above me.

'I expected to hear a voice, or perhaps feel a cold hand resting on my shoulder, but there was silence. And then, after a few minutes, the shaft of light narrowed as the sun appeared to pass westward across the slit, and total darkness came once more.' Every year since 1967, O'Kelly has returned to Newgrange for the midwinter sunrise, and every year, from his vantage point lying on the smooth sandy floor of the tomb, he has seen the bright disc of the sun fill the roofbox and the shaft of light pass down the passageway, across his face, into the recess at the back of the chamber. Its precision makes him certain that the effect was deliberately engineered.

The builders must have sat here on the hillside, perhaps for a number of years, at the winter solstice period, watching the point of sunrise moving southward along the horizon, eventually determining the point where it began to turn back again. Having established this, they could then have put a line of pegs into the ground and laid out the plan of the passage.' However, there was one more problem to resolve. The roofbox would have had to have been precisely aligned to the horizon and, as each of the stone slabs weighs about a ton, the position of the slit would have had to have been determined before the building began. Add to this the fact that the tomb was built on a hill, with the chamber 6ft (1.8m) above the entrance, and the achievement of the builders of Newgrange is all the more astounding.

Professor O'Kelly believes that this is what the builders of Newgrange intended when they aligned their tomb to the midwinter sunrise. He believes that the people whose bones were placed in the stone basins in the chamber had qualities especially valued in their society perhaps they had the gift of prophecy or the 'evil eye' and that Newgrange was designed as a temple for the spirits of the dead. As he waits in the tomb for the sun to rise on the shortest day of the year, O'Kelly is fond of speculating about the ceremonies which may have gone on there five thousand years ago.

'I think that the people who built Newgrange built not just a tomb but a house of the dead, a house in which the spirits of special people were going to live for a very long time. To ensure this, the builders took special precautions to make sure the tomb stayed completely dry, as it is to this day. Sand was brought from the shore near the mouth of the Boyne ten miles away, and packed into the joints of the great roof stones along with putty made from burnt soil. And to make absolutely sure that there would be no possibility of rainwater percolating through, they cut grooves in the roof slabs to channel it away. If the place was merely designed to get rid of dead bones, there would be no point in doing all this.'

On the day of the solstice he envisages a group of people gathered in front of the tomb's decorated entrance stone in the predawn darkness. He believes that as sunrise approached, someone climbed up to the roofbox and removed the blocks of quartz which temporarily closed it. What then went on is pure speculation. Perhaps the people made offerings to the spirits of the dead. (There is evidence of such a practice at a similar tomb in Denmark where the remains of 4,000 food vessels were found in front of the kerbstones.) Or perhaps they wished to ask the spirits of the dead for their help in the year to come.

The above article is from Arthur C Clarke's Mysterious World by Simon Walfare & John Fairley published in 1980.

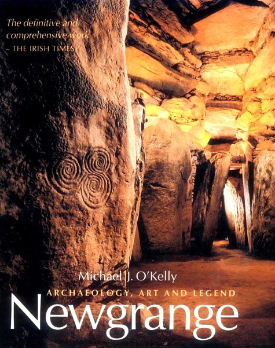

Newgrange - Archaeology, Art and Legend by Michael J. O'Kelly and Claire O'Kelly.

Newgrange - Archaeology, Art and Legend by Michael J. O'Kelly and Claire O'Kelly.

An account of the major excavation of Newgrange which was carried out by Professor Michael J. O'Kelly between 1962 and 1975.

Essential reading for the serious study of the Megalithic Tomb at Newgrange. Hardback edition first printed in 1982, Paperback edition first printed in 1988 and still in print.

In the book Professor O'Kelly presents the full results of his excavations at Newgrange between 1962 and 1975. Every stage in the excavation, interpretation and restoration of the site is described and illustrated with additional contributions from Claire O'Kelly, who collaborated in her husband's work at Newgrange from its inception.

Excavation Report Critique - by Alan Marshall

Boyne Valley Private Day Tour

Immerse yourself in the rich heritage and culture of the Boyne Valley with our full-day private tours.

Visit Newgrange World Heritage site, explore the Hill of Slane, where Saint Patrick famously lit the Paschal fire.

Discover the Hill of Tara, the ancient seat of power for the High Kings of Ireland.

Book Now

Immerse yourself in the rich heritage and culture of the Boyne Valley with our full-day private tours.

Visit Newgrange World Heritage site, explore the Hill of Slane, where Saint Patrick famously lit the Paschal fire.

Discover the Hill of Tara, the ancient seat of power for the High Kings of Ireland.

Book Now

Home

| Newgrange

| Knowth

| Dowth

| Hill of Tara

| Fourknocks

| Loughcrew

| More Places

| Labyrinths

| Local Info

| Art Works

| Articles

| Images

| Books

| Links

| Boyne Valley Tours

| Contact