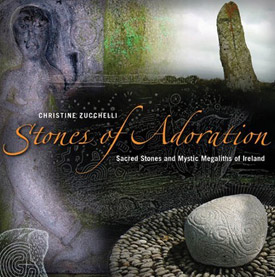

Stones of Adoration

Stones of Adoration: The Sacred Stones and Mystic Megaliths of Ireland by

Christine Zucchelli. Irish Mythology can be confusing and difficult to grasp, Christine Zucchelli

brings Irish Mythology to life in the Stones of Adoration

through well researched and accessible writing, enhanced by beautiful

photographs of Sacred Stones, Stone Circles, Standing Stones, Dolmens,

Sheela na Gigs, Ogham Stones and Wishing Stones.

Stones of Adoration: The Sacred Stones and Mystic Megaliths of Ireland by

Christine Zucchelli. Irish Mythology can be confusing and difficult to grasp, Christine Zucchelli

brings Irish Mythology to life in the Stones of Adoration

through well researched and accessible writing, enhanced by beautiful

photographs of Sacred Stones, Stone Circles, Standing Stones, Dolmens,

Sheela na Gigs, Ogham Stones and Wishing Stones.Purchase at Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk

Sacred stones and stone monuments feature the world over and Ireland is no exception. Our landscape is dotted with them, from the Royal Pillars of Tara in Meath to Meadhbh's Grave in Sligo. Since prehistoric times people have acknowledged their special nature, an unbroken link from ancient sun-oriented monuments to the present.

Some are considered the abodes of deities or otherworld ladies, some are memorials to mythical heroes and historical kings, others are reminders of the miracles of early saints. Stones of Adoration explores their secrets, myths, legends and folktales, many persisting to this day, and describes the role of sacred stones in the religious and spiritual life of modern Ireland.

Different beliefs, practices and rituals behind the notion of their magical powers and virtues are revealed, and the situations in which people resorted to them, such as determining chieftains, establishing the truth, curing sickness, and promoting fertility. This is a wonderful reminder of our spiritual past as some of these stones and monuments enter their fifth millennium and the wisdom of the Celtic tradition re-emerges.

Stones of Adoration - Introduction

One of the earliest references to the veneration of an individual stone in Ireland is a glossary to an Old Irish law tract. It dates back to the seventh or eighth century and gives a list of landmarks, among them a stone of adoration. The writer did not reveal the nature of the stone; perhaps his mind was set on one of the numerous pre-historic monuments that dot the Irish landscape, or on a natural rock of conspicuous shape or size. Writing in the early medieval period, he might have thought a stone was considered adorable for its Christian connotation.In numerous cultures all over the world, adorable or highly revered stones and stone monuments form integral parts of what we can describe as 'sacred landscapes'. Other prominent aspects of these spiritual landscapes would be sacred trees, waters, islands or mountains. The term sacred is used here to denote a spiritual or religious significance, and does not necessarily appear in its Christian understanding. Generally spoken, sacred features of the landscape come into being when humans acknowledge the presence of an anima loci, the spirit or the essence of a place.

The nature of the anima loci is determined by the concept of beliefs that prevails within a society. With history being a continuous process of cultural development and change, the spiritual and religious concepts develop and change as well, and so does the definition of what is considered sacred for a particular reason. A perfect mirror for the changing perceptions of sacredness is folklore, because it is conservative by its nature yet also absorbs new ideas and influences from outside, and likewise adapts older ideas to new situations.

The earliest spiritual concept is the animistic tradition, which regards all natural features as spirited, animated parts of the earth. Where the earth is seen as the body of her creator, natural features in the landscape are regarded as body parts of the creating earth mother or earth goddess. This concept predates formal religions, and would still surface in the oral tradition of stones that walk about or speak. When polytheistic religions emerged, the earth mother manifested herself in the shape of various goddesses; male deities appeared by their sides. Usually presided over by a father god; sacred stones and stone monuments became interpreted as the homes of goddesses and gods. Monotheistic religions finally identify sacred sites as places chosen and blessed by members of the holy family, or by saints or prophets.

The body of Irish stone folklore that lies before us today is mainly aetiological, that is, explaining the origin of stones or stone monuments. The narratives reflex the spiritual world of pre-historic to early medieval Ireland, and are only slightly influenced by later impacts from outside. The main actors of legends and tales, however, are seen through the filter of Christian spirituality; hence, ancient goddesses survive in folklore as otherworld women, hags and fairies, the gods became mythical heroes and kings, or giants; and several deities were transformed into saints. In all these guises they would usually retain their link to their traditional sacred places. Alternatively, Christian legends would demonise the ancient deities, have them overpowered by the new faith and their places of worship taken over by saints.

From the seventh century, when the monasteries of the Celtic Church had become centres of education and literary traditions, clerics compiled biographies of saints, and historical or pseudo-historical tracts, annals and genealogies. For the first time, ancient oral lore and history were preserved in writing, and these writings provide the earliest sources for the veneration and folklore of stones in Ireland.

The composers of hagiographical texts drew their inspirations mainly from Biblical texts, especially from the Old and New Testaments, and from the Lives of continental saints, but they also included motives that were current in native Celtic lore. Even deeper steeped in ancient native traditions are myths, sagas and hero tales. The tales were initially orally transmitted, and many of them might have been current from the fourth century. They survive largely in manuscripts from the twelfth century, which were written more or less completely in the Irish language and had often been copied from older manuscripts. Today, the ancient sagas and tales are conveniently grouped into four cycles of tales - the Mythological Cycle, the Ulster Cycle, the Fenian or Ossianic Cycle and the Historical Cycle or Cycle of the Kings.

The Mythological Cycle of tales - though not acknowledged by historians as a reliable source of Irish pre-history, gives particular insight into the spiritual world of ancient Ireland, and provides the most valuable pieces of information on the earliest beliefs behind the sacred stones and stone monuments of the country. The core of the Mythological Cycle of tales is the Leabhar Gabhala Eireann or the Book of Invasions of Ireland, a compilation of pseudo-historical texts which reconstruct the conquest of the country by successive groups of peoples.

The authors of such works as the Leabhar Gabhala were Christian monks; occasionally they even tried to establish a Biblical origin of the ancient Irish, and relate that it was Cessair, daughter or granddaughter of Noah, who led the first ever settlers to Ireland.' The Leabhar Gabhala itself begins with the story of Partholan and his sons. Coming from Greece, they arrived in Ireland after the Flood in about 2678 BC, and settled in the west. Centuries later, their descendants were wiped out by the plague. The people of Neimheadh, from Scythia, and his wife Macha wen the next to appear in the country.

They cultivated land in south Armagh, but were soon defeated and destroyed by the Formhoire or Formorians, who were either invaders or an already present earlier culture. Neimheadh's sons managed to escape to different parts of the world. Generations later, two rival branches of their descendants - the Fir Bolg and the Tuatha De Danann - should return. The Fir Bolg are said to have come from Greece; they divided Ireland into provinces and established the system of sacral kingship. On their arrival from Denmark or Greece (the myths differ on their provenance) the Tuatha De Danann or the People of the Goddess Danu fought and defeated the Fir Bolg and the Formorians, thus taking the sovereignty of Ireland. They had finally to submit to the Sons of Mil or Milesians, the ancestors of the present Celtic people, who came from Asia Minor and landed in the south west.

The three remaining cycles are characteristically heroic and deal with the deeds of Celtic warriors and kings. Tales are set from around the time of the birth of Christ, but again many of their motifs, plots and characters seem to derive from earlier narrative traditions. They reflect particularly Celtic spirituality, and give insight into the role of sacred stones in an aristocratic warrior society.

The ancient myths and sagas, legends and biographies of saints were read out, and consequently various episodes from the literary tradition filtered back into folklore. From medieval times, Vikings, monastic orders from the Continent, Normans, English and Scottish settlers introduced motifs from their own spiritual worlds, but their ideas were largely absorbed into the native perceptions of other-world women, heroes and saints as the divine characters behind sacred stones and stone monuments.

When people seek the divine at sacred places, when they communicate with the divine through certain rites and offerings, they recognise and reconfirm the sanctity of the location. Anciently, we have to understand these rites as ceremonies to please the divine, but as there are no written records from the customs in pre-Christian Ireland we depend on the biographies of Irish saints for the earliest information on the practical implementation of sacred stones in religious, social and spiritual affairs. The survival of archaic traits and elements as key parts of the rituals, however, indicate that some practices are considerably older then Christianity.

A prerequisite to release the indwelling powers and virtues of sacred stones is the physical contact between the applicant and the material. The act of literally connecting with the stone is an ancient trait of contagious magic, based on the belief that the essence of spirits or people to which an object owns its virtues is still alive within that object. Likewise of ancient origin is the crucial importance of the direction of movement during the performance. In Ireland, as in many parts of the world, anticlockwise motions are considered unlucky, and only suitable for sorcery and destructive magic. Popularly referred to as left-hand-wise, widdershins or tuafal, they are usually applied in cursing rituals. Clockwise or sun-wise, also known as right-hand-wise or deiseal, is the appropriate movement for constructive magic and blessings, and subsequently reserved for healing and wishing.

The early Celtic Church, distinguished by her ability to adapt pagan ideas and reinterpret them in a Christian context, had no problems with incorporating older traits into her own complex of religious observances. Only from the twelfth century, when ecclesiastic reforms from the Continent had swept over to Ireland, should the Church hierarchy change her attitude and begin to consider semi-pagan practices as superstitions. Monastic orders from the Continent were encouraged to settle in Ireland and to bring the Celtic Church spiritually and structurally in line with the principles of the Papacy.

All over the country, stone churches and monasteries were built, usually in the Irish Romanesque style with its arched doorways and figural carvings. Replacing earlier timber structures and open-air altars, the churches should provide a venue for controlled and organised Christian observances. Whether it was desired by the orders or not, it seems that the cult of sacred stones was to a certain degree transferred or extended from sacred places in the landscape to the stone carvings in and about those new religious centres.

An even deeper influence on the role of sacred stones in folk customs and popular religion had the political and social development of the country from the late medieval period. In 1155, Pope Adrian IV (the only English pope in history) granted the sovereignty of Ireland to the Anglo-Norman king of England, Henry II. Justified as a tactical move to aid the process of Church reform and to copper-fasten the papal influence on spiritual matters in the country, it was practically a licence for the ensuing Norman and English conquests of Ireland.

The authority of the Papacy in Ireland began to decrease considerably from the 1530s, when King Henry VIII had set up the independent Anglican Church (in Ireland established as the Church of Ireland) under the supremacy of the English monarch. The Reformed Church did not have the cultural insight nor the language for large scale conversions; although declared the one and only official Church, she became the Church for those loyal to the English Crown, while wide sections of the native Irish population did not convert and held on to the Catholic faith.

Irish Catholicism in those days still held many elements and views of the early Celtic Church. On the Continent the Counter-Reformation, inspired by the Council of Trent (1545-1563), had widely succeeded in erasing semi-pagan practices from Catholic devotion. Papal attempts to modernise Catholicism in Ireland came to an abrupt end with Cromwell's offensive in 1649. The persecution of the Catholic faith under Cromwell's regime, followed by oppressive laws in the aftermath of the Battle of the Boyne at the end of the century, deprived the Catholic Church of the structure and means to effectively eliminate what it considered superstitious observations.

At the same time, the political circumstances created an atmosphere that allowed magic practices to flourish, and Irish Catholicism developed an even deeper popular character with an eclectic mixture of orthodox and pagan elements. Often ridiculed by hostile contemporary observers, many of these archaic customs and traditions were, in fact, social and spiritual utilities created and fostered by oppression and poverty. In times of crisis or emotional unrest, people resorted to healing stones where no proper medical service was available, and to protective stones to find truth, justice and revenge when they could not trust the courts. Due to the destruction of Church property, Irish Catholics had none or few churches to attend, and Mass was offered in private houses or at the ancient ceremonial places like holy wells and sacred stones.

It was only after Catholic Emancipation in 1829, and especially after the famine years In the 1840s, that the Church hierarchy In Ireland gained sufficient power to modernise herself and to rid Catholic devotion from unconventional archaic practices.

The leading figure of this reform was Paul Cullen, Archbishop of Armagh from 1840 to 1870. Determined to spiritually structure Irish Catholicism along the lines and principles of Rome, Cullen banned pilgrimages to holy wells, suppressed the celebration of Mass in private houses and at Mass Rocks, and ordered or encouraged the removal or destruction of several sacred stones. Under his supremacy, new churches were built, often of impressive dimensions. Aiding his intention to transform religious worship from outdoor affairs into well-organised public services in consecrated buildings, they were at the same time demonstrations of the rise and increasing power of the Catholic Church in Ireland.

Characteristically, there was a tendency to dedicate these new churches to the Virgin Mary rather than to a local patron saint. From the times of the Crusades, a passionate veneration of Mary has spread throughout western Christendom. On the Continent, encouraged by the Catholic Church, countless sacred places and chapels have since been re-dedicated, with Mary replacing the earlier patron saints. In Ireland, re-dedications are rather scarce; the love and devotion to the Virgin, however, is apparent in the erection of statues and Lourdes-style grottoes throughout the country, and in her intense veneration in the context of apparitions.

At about the same time, when older popular traditions and religious practices began to lose their significance in people's everyday lives, a rise of national sentiment and growing interest in the cultural heritage of the country became apparent among scholars from various disciplines. Antiquarian societies such as the Royal Irish Academy or The Royal Society of Antiquities in Ireland were founded to research archaeological, historical and folkloristic aspects of Irish culture. Their reports, together with the letters and memoirs of the Ordnance Survey, established in 1823, contributed to the preservation and documentation of popular traditions.

An invaluable source of Information on all aspects of folklore is the manuscript collection of the Irish Folklore Commission in the Department of Irish Folklore at University College Dublin. The commission, established in 1927 as An Cumann le Béaloideas Éireann or the Irish Folklore Society, had focused on a systematic documentation of folk traditions and oral lore. Since 1956, the Ulster Folk and Transport Museum in Bangor is committed to illustrate and preserve the traditions of people in the North.

References regarding the practical use of stones are numerous in surveys, travellers' accounts and reports of antiquarians, and in the folklore collections of the Irish Folklore Commission. They give a lively picture of public performances in the context of pilgrimages and patterns, and of rather private observances at healing, swearing, wishing and cursing stones. The most detailed data relate to the period from the early nineteenth to the early decades of the twentieth century and show that, in spite of a certain decline due to the suppressive measures in the course of Cullen's Church reform, most of these practices continued at least into the middle of the last century. With the rapid urbanisation, modernisation and industrialisation of Irish society throughout the last decades, the old popular traditions came again under serious threat. Fortunately, there are clear indications that they are not entirely lost and gone.

Christine Zucchelli first visited Ireland in the 1980s. Captivated

by the wealth of the country's heritage, after graduating from Innsbruck

University, she studied Irish Folklore at University College Dublin and

travelled the country in search of the myths, legends and folklore behind

the veneration of particular stones.

Christine Zucchelli first visited Ireland in the 1980s. Captivated

by the wealth of the country's heritage, after graduating from Innsbruck

University, she studied Irish Folklore at University College Dublin and

travelled the country in search of the myths, legends and folklore behind

the veneration of particular stones.

Christine worked as a guide and organiser of special interest tours to Ireland but now concentrates on research into aspects of the sacred landscape. She lives in West Clare and Innsbruck.

Purchase at Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk

Boyne Valley Private Day Tour

Immerse yourself in the rich heritage and culture of the Boyne Valley with our full-day private tours.

Visit Newgrange World Heritage site, explore the Hill of Slane, where Saint Patrick famously lit the Paschal fire.

Discover the Hill of Tara, the ancient seat of power for the High Kings of Ireland.

Book Now

Immerse yourself in the rich heritage and culture of the Boyne Valley with our full-day private tours.

Visit Newgrange World Heritage site, explore the Hill of Slane, where Saint Patrick famously lit the Paschal fire.

Discover the Hill of Tara, the ancient seat of power for the High Kings of Ireland.

Book Now

Home

| Newgrange

| Knowth

| Dowth

| Hill of Tara

| Fourknocks

| Loughcrew

| More Places

| Labyrinths

| Local Info

| Art Works

| Articles

| Images

| Books

| Links

| Boyne Valley Tours

| Contact